EVERY YEAR THEY COME, THOUSANDS OF STUDENTS WHOSE DREAMS HELP DRIVE BOSTON, BUT WHO MUST INCREASINGLY SCROUNGE FOR HOUSING OFF CAMPUS. A GLOBE INVESTIGATION FINDS THEY ARE EASY TARGETS FOR SCOFFLAW LANDLORDS WHOM THE CITY SEEMS UNABLE, OR UNWILLING, TO CONTROL.

This story was reported by Globe Spotlight team reporters Jenn Abelson, Jonathan Saltzman, Casey Ross and Todd Wallack, and editor Thomas Farragher. It was written by Farragher and Ross.

THE SCREAMS for help. The harrowing leaps from smoky rooftops. The young life lost.

The nightmare fire on Linden Street that killed a promising young Boston University undergraduate, Binland Lee, was only a few days past when Josh Goldenberg returned to the street in Allston where he once lived.

The BU student stared at the remains of number 87, an old home reduced to charred wood and ashes. He’d heard how Binland had been found in the attic bedroom she’d loved, in an illegal apartment with only one way out — through the smoke and flames.

“I just thought,” he said, “that could have been me.” And it nearly was.

A year earlier, the house across the street had gone up in flames and Goldenberg had lived through it — barely. He had escaped by jumping from an attic window, suffering major head trauma and neurological problems that linger still.

HANDOUT

Goldenberg, who was in a coma for nearly two weeks and spent three months at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, still suffers form double vision, balance problems and other issues related to his brain injury.

His house and Binland Lee’s were alike in other ways. Both were illegally overstuffed with undergraduate tenants; neither had been inspected by the city in years. In the aftermath of the back-to-back calamities on Linden Street, city officials promised to intensify their efforts and crack down on violators, to better protect the tens of thousands of students who live off campus.

But that’s not what happened.

A Globe Spotlight Team investigation has documented what Lee’s death and Goldenberg’s near-death alone make tragically clear — that Boston’s efforts to safeguard students and protect city neighborhoods from real estate investors transforming them into college rental ghettos have failed by almost every measure.

A collision of greed, neglect, and mismanagement is endangering young people in America’s college capital while enriching some absentee investors — landlords who maximize profits by packing students into properties — and universities that admit many more students than they can house.

It is a heedless calculus that begins with the flood of student renters and the landlords who freely defy housing codes, and is enabled by city inspectors who simply are no match for the health and safety challenges that result.

The city checks a small fraction of Boston’s rental units each year, the Globe found, and antiquated record-keeping leaves the city with no effective way to track repeat offenders.

Boston requires landlords to have their apartments inspected every time new tenants move in. But few do. Last year, officials conducted only 2,304 of these inspections out of roughly 154,000 rental units in the city of Boston. That’s one out of every 67 apartments. By the city’s own conservative estimate, ordinary turnover should result in 44,000 of just this one type of inspection every year.

And there is no doubt what inspectors would find if they performed this basic work: Students living in filthy units where doors don’t lock or windows don’t close, where heat doesn’t work or it won’t ever stop, where rodents and pests are daily visitors, where bedrooms are crammed illegally into dingy basements or into fire-trap attic apartments.

Especially, in cases of illegal overcrowding — as in both Linden Street homes that went up in flames — citations for overcrowded conditions appear to be nonexistent.

Even after those fatal and near-fatal fires, neither property owner was cited for this obvious violation.

Indeed, pressed by the Globe, the city could not turn up even one student overcrowding citation.

In its investigation of off-campus housing in Boston, the Spotlight Team reviewed hundreds of court files and thousands of computerized records of complaints to city inspectors and 911 calls; examined property records and internal city e-mails; and interviewed hundreds of students, landlords, and city and university officials. The investigation revealed:

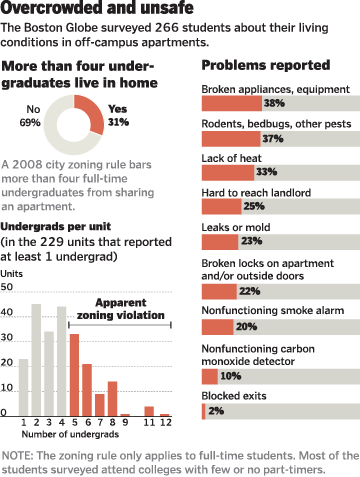

■ Illegal, overcrowded apartments riddle the city’s college neighborhoods, including a significant number in violation of a city zoning rule barring more than four full-time undergraduates from sharing a house or apartment. Globe reporters and correspondents visited block after block of rental properties in student-rich enclaves — near BU, Boston College, and Northeastern University — and found overcrowding a fact of life.

And in a Globe survey of 266 students living off-campus in Boston, nearly one-third of students questioned said at least five undergraduates were sharing living quarters. In sections of Brighton near Boston College, where most juniors are not provided on-campus housing, 80 percent of the students surveyed said they had more than four undergraduates in their apartments. Of the 15 student apartments surveyed on Gerald Road, a short street within walking distance of Boston College, only three housed four or fewer undergrads.

“It’s become an absolute community crisis,’’ said Valerie K. Frias, associate director of theAllston Brighton Community Development Corporation. “The landlords are taking advantage of the situation, pulling out massive profits and putting very little — if any — work back into the properties with very little regard for public safety or human life.’’

■ Trailing hard on the heels of overcrowding are health and safety issues, ranging from the kind of deadly peril that claimed Binland Lee to side effects of squalor of a more ordinary kind. A Globe analysis of records found that four student-rich ZIP codes, when adjusted for population, have 50 percent more complaints overall than the citywide average in more than a dozen categories, including mold and mice infestation as well as more serious safety concerns such as missing or broken carbon monoxide detectors and overcrowding. The ZIP codes covering Allston, Brighton, Mission Hill, and Fenway have generated more than 14,000 complaints to inspectional services over the past eight years.

And rodents are everywhere — more than 3,500 complaints since 2006, just from these student rich areas.

DARREN DURLACH/GLOBE STAFF

This house on Linden Street in Allston was infested with rodents, had electrical problems, and was in overall disrepair. Still, the student tenants paid more than $5,000 a month in rent.

■ The Inspectional Services Department, or ISD, the city’s chief code enforcement agency, is no match for the flood of complaints and routinely misses health and safety problems that create dangerous, sometimes life-threatening conditions. The agency, which relies largely on paper files, is unable to give firm answers to basic questions, like how often landlords are cited for housing violations. And when records of violations are filed electronically, the agency doesn’t mine the data to track which landlords have been cited the most.

There is, as a result, only a limited capacity to respond to chronic offenders. And even when their misconduct is so egregious as to be impossible to ignore, the most notorious of Boston’s landlords escape with what amount to administrative slaps on the wrist.

■ Along with landlords and ineffective city regulators, there is a third powerful force contributing to overcrowding and the hazards that flow from it. Several of the colleges and universities that import these thousands of young and eager new Bostonians have promised to house more of them on campus, and then have broken that promise. A growing flood of student tenants is the result — a ready market for landlords short on scruples.

The number of undergraduate and graduate students living off campus in the city soared 36 percent to more than 45,000 from 2006 to 2013, according to reports filed with Boston’s city clerk by private universities with a Boston presence and data that three public colleges provided the Globe. Many of the additional students are pouring into neighborhoods like Mission Hill, Fenway, and Brighton.

And those figures undercount the number of off-campus students, because they exclude nearly 8,000 Northeastern University co-op students — many of whom live in the city. It also does not include the hundreds of MIT students living in Boston in sororities and fraternities, and at least 1,000 Harvard students who reside in Boston but attend classes in Cambridge.

Local schools did add some new dorms over the last decade — but only enough units to accommodate less than half of the tens of thousands of added students they’ve accepted during that time. The shortfall reflects a national trend. In state after state, surging college enrollments have outpaced construction of dorms, according to federal data, pushing students off campus.

The dorm space that is available can be prohibitively expensive, further nudging students to look elsewhere. Median room and board costs for Boston area schools climbed 59 percent from 2000 to 2012, nearly double the inflation rate.

A single room with a shared bathroom at BU, with the required meal plan, costs $16,320 for two semesters. That means students who pay $700 to $1,000 a month for off-campus quarters could save significantly, especially since many sublet during the summer.

■ Overcrowding and its health and safety side effects have taken a harsh toll on city neighborhoods.

Today, in the triple-deckers, duplexes, and red-brick apartment complexes that surround the city’s biggest universities a kind of real estate black market has blossomed.

There, illegal overcrowding has, in some cases, created a maddening paradox: While individual properties have deteriorated, overall housing prices have skyrocketed, making it difficult if not impossible for middle-class families to buy houses or afford rents.

“The price of triple-deckers and duplexes has just exploded,” said Barry Bluestone, director of the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University. “There is an almost unlimited demand for that housing.”

On Mission Hill near Northeastern, the price escalation for three-family houses is breathtaking. Many now sell for well over $1 million, more than double the 2013 median price for three-families in the broader Roxbury neighborhood that surrounds Mission Hill, according to a Globe analysis of property records.

It has also changed the face of some neighborhoods near college campuses, where investors have scooped up one property after another. For instance, the share of owner-occupied properties in Mission Hill’s main ZIP code has declined from 52 percent in 2003 to 42 percent in 2014 — a bigger decline than anywhere else in the city. Absentee landlords have also become more dominant in student-rich neighborhoods in the Fenway and Brighton over the past decade.

In a neighborhood of nearly 200 homes off Commonwealth Avenue near Boston College, 26 percent of the properties have switched to investor ownership since 2003, a Spotlight Team analysis found.

And the homeowners who remain frequently complain about the noisy tenants. As one might expect, many of the 911 calls about loud parties are clustered in neighborhoods packed with students. Boston Police recorded nearly 13,000 party calls in eight years from Allston/Brighton alone, more than any other police district.

ARAM BOGHOSIAN FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

Longtime residents of college neighborhoods, like this one on Foster Street in Brighton, say late-night rowdy parties cut into their sleep and their quality of life.

As Boston’s university population increasingly spilled amoeba-like into college neighborhoods, then-Boston City Councilor Michael P. Ross had a name for that growth as he successfully argued for the ordinance combating overcrowding in 2007.

“Shadow campuses,’’ he called the student incursions.

And today, more than six years after the passage of the no-more-than-four initiative, those shadows are growing longer — and darker.

TURNING A BLIND EYE

IN THE WORLD of real estate — where fortunes can be won and lost in the boom or bust of the market — investing in a rental property in one of Boston’s student neighborhoods is as close as it gets to a sure thing.

Many multifamily houses in Mission Hill, Allston, and Brighton produce more than $100,000 a year in rental income. That means their owners can pay their expenses while also raking in tens of thousands in cash a year. If they decide to sell, ever-rising rents will allow them to unload their properties at a higher price to the next investor.

With so much money to be made, the temptation to break the overcrowding law can be too much to resist for many landlords and the rental agents they hire to market their units.

The zoning code could not be clearer: No more than four undergraduates can share a single apartment unit. And the reason for the restriction is plain as well — packing in more students tempts landlords to carve up the units in all kinds of unplanned-for ways. They crowd passageways, close off exits, make bedrooms out of spaces — like Binland Lee’s garret — where the hazard is only apparent when disaster strikes.

But in the neighborhoods where overcrowding is most commonplace, student tenants and those who rent to them often disregard the law.

About two-thirds of the students in the Spotlight Team survey said they oppose the measure designed to stop them from cramming into such rental units. They prefer to pretend the restriction doesn’t exist.

Nick Casale of Wellesley said he and his 11 BC roommates are each paying $710 a month to live together in two units on Gerald Road in Brighton. And he said Boston College officials must be aware of that rental market calculus.

“These are the houses for college kids that are near BC and you have to fit so many kids in here to make it realistic,’’ Casale said, as he prepared to move into his new off-campus home last September.

That outlook finds a willing accomplice in those whose business is built on renting to students.

When Globe correspondents — themselves students at local colleges — visited rental units in the company of real estate agents and landlords, they confirmed first-hand what the Spotlight Team heard in dozens of interviews across the city’s student landscape: The overcrowding measure is treated as little more than an easily thwarted nuisance.

A Globe correspondent asked a Brigham Circle agent last summer if five undergraduates could move into an apartment on Mission Hill. No problem, he said, sketching a common way to work around the city’s rule: Four students would be listed on the lease while all five would provide the agent with cosigners to guarantee the rental income.

The agent described the city’s zoning rule contemptuously, as little more than a way “to stop stupid drunk college kids from falling off balconies.’’

A couple of days later in Allston, the no-more-than-four ordinance was dispatched with equal ease.

“I’m OK with six people,’’ said an agent who showed a Globe reporter a unit on Gordon Street. “I’m OK with doubling up [with multiple people in rooms]. Just don’t piss off the Asian woman next door.’’

Globe correspondents viewed some 25 apartments with brokers, most of whom were willing to violate the city’s antiovercrowding measure as long as students were willing to pay a slightly higher rent. During its investigation, Globe reporters visited more than 100 apartments where it was not uncommon to see living and dining rooms — as well as dens, attics, and basements — that had been converted into bedrooms.

Bryan Glascock, the inspectional services commissioner, said his inspectors are virtually powerless to enforce the overcrowding restriction because they can’t act unless invited onto the premises or have strong enough evidence of emergency conditions to persuade a judge to issue an administrative search warrant — both rarities.

He doesn’t claim to be understaffed, but records show the department’s staffing has barely budged over the last decade.

The city has recently taken steps to change that.

This fiscal year, the agency received a 10 percent increase, to $17.6 million — money that paid for five additional inspectors for Boston’s new rental reinspection program, requiring landlords to register their units with the city and submit to inspections every five years for potential violations of the sanitary and building codes.

But even with that staffing bump, the agency is still only planning to inspect about half of the 31,000 apartments each year that are covered under the new rental ordinance. It expects property owners to hire outside agencies to carry out the rest. It’s a daunting task that would come on top of the 15,000 to 18,000 other housing inspections that Glascock said the agency conducts in a typical year in response to complaints.

Like mayors before him, Martin J. Walsh has promised relief to the neighborhoods and safe housing for the students.

When he was a candidate last summer, Walsh lamented inspectional services’ staffing levels and anemic budget, saying it rendered the agency “a paper tiger.’’

“The landlords abuse the kids that come to the schools by packing them in as many as they can to an apartment,’’ said Walsh. “We will not stand for it.”

Boston police Sergeant Michael C. O’Hara, who oversees efforts to curb student misconduct in Brighton and Allston, said Walsh is on the right track.

He said most of the problems — often alcohol induced — can be traced to students living in overcrowded quarters that quickly become magnets for large and rowdy weekend parties.

On a frigid night in December, before Saturday night blended into Sunday morning, O’Hara was breaking up a huge bash on Gardner Street in Allston hosted, he said, by students from the Berklee College of Music.

“I suggest if there’s anyone in here underage you get them out,’’ he said after a startled tenant answered the back door and told him he had “40 or 50” guests. Within 15 minutes, nearly 100 young adults had spilled out of a basement where music had blared and a keg of beer had been tapped.

ARAM BOGHOSIAN FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

Boston Police Sergeant Michael C. O’Hara breaks up a large, alcohol-fueled party in Allston where overcrowding -- and the health and safety issues that accompany it -- are chronic concerns.

RISKS TO HEALTH, SAFETY

MOST COLLEGE STUDENTS arrive in Boston with huge tuition bills and a yearning for independence.

They are often first-time renters and typically know little about their rights as tenants, or the hazards that might await them in a densely packed city with some of the nation’s oldest rental apartments.

The Spotlight Team’s investigation not only found chronic overcrowding, but also that students are living in units with grievous code violations, some of them life-threatening.

How bad is it out there?

■ A Museum of Fine Arts student and his friends headed out to a third floor deck in Mission Hill to enjoy an early fall evening last September. The unpermitted structure collapsed, leaving a dozen people with injuries, among them concussions and a fractured heel. The city later cited the property owner.

JOHN TLUMACKI/GLOBE STAFF

A Museum of Fine Arts student and 11 others were injured after this illegal third floor deck in Mission Hill collapsed. The city later cited the property owner.

■ A Fisher College student noticed that an outside door to her Commonwealth Avenue apartment building was held open day and night with electrical wire. Concerned for her safety, she said, she complained to her real estate agency. But nothing was done. Days later, on Sept. 21, 2008, she and her roommate were brutally raped at knifepoint in their apartment by an intruder. The women settled a lawsuit against the landlords and real estate firm last fall for $900,000, according to their lawyer.

■ A BU law student moved into an apartment in Allston in September 2008 and two months later noticed something odd — small, itchy welts on her hands and arms. She first believed it was caused by law-school stress. Four months later,a doctor blamed it on bedbugs, an all-too-common problem in student neighborhoods. After the landlord failed to eradicate the problem, she broke her lease and sued him and her real estate broker, who together later settled for more than $5,000 in 2011.

■ BU roommates, watching television last June, smelled smoke and then saw it seep through the floorboards of their overcrowded second-floor apartment in Allston. A frayed extension cord in the downstairs unit was to blame. The six displaced students had no ready way to reach their landlord. They had never met her and didn’t even know her name.

If one goal of the antiovercrowding measure was to dampen the overheated student rental market that has pushed out longtime residents and destabilized neighborhoods, another was to promote student safety.

And in their full-throated support for the no-more-than-four restriction, university officials vigorously waved the flag of safety.

The appeal made by the Wentworth Institute of Technology was typical. Two senior Wentworth officials wrote City Hall to applaud efforts to keep students from living on outdoor porches and carved-up living rooms.

“These activities are dangerously unacceptable and need to be stopped,’’ they said.

BU’s president Robert A. Brown said he was concerned, too.

“What really worries me is that the landlords in a lot of these apartment buildings aren’t meeting the standards, both for code and egress, and finally that they’re turning a blind eye to residences that are overpacked,” Brown said in the aftermath of Binland Lee’s death.

The day after the fatal fire, Frias, the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation official, suggested one remedy, urging universities to share the addresses of their off-campus students so city officials can build a database and spot overcrowded units.

Almost every college and university has repelled the city’s efforts to obtain that data. BU became the first college to comply last May when it disclosed the addresses where five or more BU students lived. But inspectional services has yet to mine that list to cite offending landlords.

Asked whether it would help if every college provided off-campus addresses, an agency spokeswoman agreed that it would. Then she added: “But staffing would not allow oversight.’’

“There are some legal disagreements about whether or not colleges can in fact give us that information,’’ said BRA director Peter Meade before he left that post earlier this year. “Our position is a very strong one that they can and should.’’

If the city knew precisely where to look, they would be alarmed at what they would find.

As part of its investigation, the Globe hired North Shore health inspector and registered sanitarian Rosemary Decie as a consultant to inspect units with the approval of their young tenants. In a single afternoon, Decie found nearly 50 code violations in three units that are home to university students.

SCOTT LAPIERRE / GLOBE STAFF

Rosemary Decie, a registered sanitarian and Globe consultant, found nearly 50 code violations -- including health and safety threats -- in a single afternoon at three student apartment units, including 25 at this one on Linden Street in Allston.

At a single-family home on Pratt Street, in the heart of a heavily populated student neighborhood in Allston, Decie found two serious violations in a unit rented by Emerson College students: the absence of carbon monoxide detectors and an obstructed second egress through a first-floor bathroom. The door there was barricaded by a 2-by-4 piece of wood, an obvious impediment in the case of an emergency. She called it a “major violation.’’

“You’re not allowed to have a second egress through a bedroom or a bathroom or any locked door,’’ she said.

Across town, in a basement apartment unit on Everett Street in Allston, Decie found serious safety hazards in the home of a Fisher College sophomore. One outside door did not lock — a surprisingly common and dangerous condition — and the second egress from the apartment is through a dark room that is a maze of hot water heaters. “He is not safe in the apartment,’’ she said.

Even on fire-scarred Linden Street trouble remains.

When Decie inspected a two-toned tan house there, next door to the home in which Binland Lee died, she found 25 code violations: the basement door missing its knob, a large dead mouse by the hot water heater, mouse droppings behind the living room couch, a hole in the ceiling over the kitchen sink, and a loose banister on the third floor.

When the property’s landlord, Nirmal Sharma, was reached at his home in California, he seemed surprised by what the Globe found.

“That sounds awful. I did not know that,’’ he said in a telephone interview. “It looks like I have to find a better property manager.’’

In a voicemail to the Spotlight Team hours later, Sharma said he had consulted with his property manager who asserted that the house was fine in September. “Everything that you told me must have been done after that,’’ the landlord said.

And then he asked the Globe for a list of problems so he could have them repaired.

One of Sharma’s tenants, BU junior Terry Bartrug, called the house a “fire hazard’’ and disputed the idea that it was tip-top in September.

“If we ever complain about anything, they’re like, ‘Oh man, you should have seen it before,’’ Bartrug said. “But it’s still not freakin’ livable for us.’’

Within weeks, Sharma would have to deal with more than his tenants’ complaints: the antics of the students themselves.

In late February, Bartrug and three of his housemates were jailed after police broke up a large party at which they found many minors and more than 1,000 beer cans.

Days later, Sharma — clearly fed up — said he planned to put his investment property up for sale. It went on the market in April for $800,000, according to the listing. “Needs some work but this is for sure a great investment opportunity!”

Most city colleges, citing privacy concerns, say they have limited authority to patrol the living conditions of their students in the neighborhoods.

Jack Dunn, Boston College’s director of public affairs, said he was unaware of the large number of BC students crowding into apartment units within walking distance of the college.

“I’m surprised personally that you found 12 students living in one house,’’ Dunn said. “That frightens me from a safety perspective.’’

But it’s not as if BC doesn’t know where its students are living.

It does.

At a meeting in the university’s Robsham Theater last fall for the nearly 1,300 juniors who are living off campus, Kristen O’Driscoll, assistant dean for off-campus life and civic engagement, reminded her undergraduates that they had to send her their off-campus addresses or risk being shut out of the BC computer system.

When a representative from the inspectional services agency attending the session reminded the BC juniors that no more than four of them could lawfully live together in a single unit, one young woman in the rear of the theater struggled — unsuccessfully — to stifle an are-you-kidding-me guffaw. Four rows in front of her, two BC juniors turned to each other and exchanged tight smiles as one jabbed his elbow into the ribs of his friend.

When BC junior Daniel Terceiro, who said he lived last fall with seven roommates in an apartment owned by an absentee landlord from Chicago, ran into housing trouble, he sought the help of a BC employee, Steve Montgomery. Montgomery is known colloquially as BC’s off-campus RA, or resident assistant, who monitors the neighborhood for loud parties and behavior that frequently draws the ire of long-time local residents.

Terceiro, a Lexington native subletting the apartment, said he and his housemates had been cited for loud parties. And they met last semester with Montgomery about how best to deal with their landlord.

“If we talk to a representative of the university and have a meeting with them with seven of our housemates and say we’re housemates, it’s not like they send us a letter saying, ‘You’re breaking the rules. You’ve got to stop right now,’ ’’ said Terceiro. “They let it go.’’

Montgomery said students are reminded multiple times about the city’s antiovercrowding rule.

And Dunn, the BC spokesman, said federal student privacy laws preclude the school from sending the city its students’ off-campus addresses — even though federal regulators say schools who designate addresses as directory information are generally permitted to do so. And in an e-mail exchange with the Globe in March he seemed to reconsider his earlier comments about the impact of a large number of students living in homes near campus.

“It cannot be said that those units that may have more than four students living together to meet the high cost of rent will result in the endangerment of students,’’ the BC spokesman said.

PROMISES BROKEN, UNFULFILLED

BOSTON’S STUDENT HOUSING problem has slowly enveloped whole neighborhoods over the decades. But even as the damage has grown more severe, inundating entire neighborhoods with noisy students and reckless real estate speculators, the city’s political leaders, universities, and urban planners have struggled to stanch it.

The Boston Redevelopment Authority, the city’s planning arm, has become an imperfect — some critics say untrustworthy — arbiter of the bitter debate between the colleges and their neighbors over housing.

When residents complain about student noise, or press the universities to build more dorms, the BRA often brokers agreements requiring the colleges to build more units to get their students out of the neighborhoods by specific dates.

ARAM BOGHOSIAN FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

Longtime Allston resident Robert Dunne said he has seen his Pratt Street neighborhood deteriorate as many houses changed from owner-occupied to rentals.

But the agency has allowed some deadlines to pass without the benchmarks being met, and neighbors who were asked to be reasonable and compromise are asked to compromise yet again, with assurances that their concerns will be addressed the next time around.

In early 2010, for instance, Mission Hill residents accused Northeastern University of reneging on a commitment to limit its undergraduate enrollment to 15,000.

The college’s undergraduate enrollment in the fall of 2009 stood at 15,585, with half of those students living in off-campus housing. “They’re taking an already difficult rental market and making it worse,’’ said Ross, then the president of the Boston City Council.

Northeastern, at the time, defended its creeping undergraduate enrollment as being within an acceptable range.

Other agreements brokered over the years remain unfulfilled, including promises to terminate leases for hundreds of beds Northeastern rents in private buildings, more than half of which are now controlled by one of the city’s most notorious landlords.

When Northeastern unveiled its most recent 10-year master plan in June 2012, it included no dorm construction at all. At the time, Linda Kowalcky, then a BRA deputy director, lamented that a presentation by Northeastern made scant mention of either the neighborhood problems or the need for more on-campus housing.

“Do they listen to us at all???” Kowalcky wrote to a colleague, BRA planner Gerald Autler, in a 2012 e-mail obtained through a public records request. After months of debate, Northeastern eventually agreed to build 600 more dorm beds within five years, but that’s still 400 shy of what some neighbors had demanded in that timeframe.

To many Mission Hill residents, the shortage of campus housing, and the rowdy students it brings to their neighborhood, remains a constant irritant.

“Even though it started out as parties, what it has turned out to be is a loss of our neighborhood,’’ said Susan St. Clair, who moved to Mission Hill in 1970. “And we love our neighborhood. We’ve lost families with little kids and teenagers. We’ve lost older people. It’s tipping the balance.’’

While Northeastern’s overall enrollment jumped 32 percent between the spring of 2006 and spring 2013, the number of the college’s students living off-campus in Boston soared 67 percent to 8,322 during the same period.

Why hasn’t NU built more dorms?

The home of the Huskies insists it is trying. As part of a deal to rent more classroom and office space near the campus in late 2010, Northeastern agreed to partner with a student housing developer to lease about 720 dorm beds behind the YMCA on Huntington Avenue. The project, delayed by lawsuits, is expected to be completed next year.

It would be unfair to simply blame the deadlock over student housing on the universities’ intransigence. Suffolk University, which housed only 21 percent of its undergraduates in spring 2013, scrapped plans to construct a dorm in Beacon Hill several years ago in the face of neighborhood opposition.

And in Brighton, a counter-intuitive battle is unfolding over Boston College’s plan to build enough housing to keep all of its students on campus. That would be welcome news in most college neighborhoods.

But the fight at the Heights is about expanding campus boundaries.

Although BC’s enrollment has held steady at roughly 9,000 undergraduates, the school and a group of nearby neighbors are locked in a fiery dispute over BC’s shifting promise that it would not build dorms on property it acquired from the Archdiocese of Boston across Commonwealth Avenue even closer to the neighbors in Brighton.

In 2008, then-Mayor Thomas M. Menino stepped in to say BC should build dorms first on its traditional campus. The proposal is now on hold.

BC says it can’t win. Its closest neighbors want students out of the crammed multifamily units around the college but object to the proposed new dorms on its expanded campus.

Neighbors charge that BC is presenting a false choice. They argue it should drop aesthetic objections to building more — or bigger — dorms on its main campus.

Maria Rodrigues, an associate professor at the College of the Holy Cross who lives nearby, argued that building dorms in the middle of her neighborhood is not the solution — a sentiment that seemed to resonate with the project manager the BRA had assigned to the BC expansion plan.

“They are invading a community, and living up on Mission Hill with NU students, I sympathize,’’ John Fitzgerald wrote in an internal BRA e-mail obtained by the Globe. “It really brings down the potential of making Allston/Brighton and Mission Hill great places to live.’’

MAKING A NEAR-FATAL CHOICE

ARAG-TAG CONVOY of U-Haul rentals and battered pickup trucks descended on Boston’s college neighborhoods under a gentle morning rain on move-in weekend last September.

JOHN TLUMACKI/GLOBE STAFF

Parents are often shocked at the conditions of off-campus housing, but students relish the freedom and money saved.

It was the familiar, chaotic scene signaling that one of America’s biggest college towns was back in business.

There to greet the returning students was a phalanx of 60 officials from inspectional services and other city departments, including the agency’s chief, Glascock.

The inspectors marched through an Allston neighborhood, writing 800 citations, including one house where rats had eaten through woodwork and burrowed into the soil.

By now, longtime — and long-suffering — residents know the ritual show of force is fleeting and ineffectual.

Even as they were spotting ratholes, broken banisters, or worthless smoke detectors, the city inspectors were missing the flood of students who were carrying mattress after mattress into illegally overcrowded units.

Indeed, as Glascock and his inspectors fanned out on Pratt Street, 10 minutes away in Brighton, 13 BC women quietly unpacked themselves into a house at 24 Gerald Road, five downstairs and eight upstairs. At the house next door, 12 BC men hauled belongings into their units. Seven on the second floor. Five on the first.

It was a profitable day for the man who owned those homes, Anthony DiMeo, a Stow businessman, who first struck gold in the shadow of Boston College’s manicured Chestnut Hill campus, in the spring of 2005.

DiMeo bought a light gray two-family home on the hilly street off Commonwealth Avenue and the monthly rents he collected from college students proved so profitable that he doubled down three years later.

He bought the house next door in early 2008, bringing his total investment in the neighborhood to $1.8 million.

When the city threw sand into the gears of DiMeo’s purring real estate machine by enacting the no-more-than four regulation eight weeks later, DiMeo and three other landlords rushed into court.

They said their apartment houses “do not constitute ‘overcrowded’ student housing in any way.’’ They assailed the rule as unconstitutional, a challenge a state judge dismissed in 2010.

At first blush, it looked like DiMeo could no longer fill his houses with BC students and fill his pockets with the monthly income they — or their parents — mailed to him each month.

The gold rush on Gerald Road, it seemed, was over.

Except it wasn’t.

DiMeo, who has since sold one of his properties, simply ignored the new zoning restriction, according to his tenants.

Asked how many student tenants he has and how much rent they pay him, DiMeo declined to answer.

“The colleges don’t have the capacity to house the number of students they accept,’’ he said in a brief telephone interview.

The flouting of the overcrowding rule and the potential consequences that accompany it are something that Anna Braet and Josh Goldenberg know painfully well.

Braet, a BU student who was staying with a friend the night of the fire at 84 Linden St., jumped from a window one story down from Goldenberg’s third floor unit and fractured her spine during the escape in January 2012.

The cause of the fire was never determined.

JOHN TLUMACKI/GLOBE STAFF

Boston University student Josh Goldenberg was in a coma for nearly two weeks after he jumped from an attic window to escape a fire at 84 Linden St. that destroyed the house, which was later razed.

Both of them sued the former property owners for violating the no-more-than four regulation, among other problems, and recently settled the case. An attorney for the former owners said they purchased the building months before the fire and had no idea it housed more students than the ordinance allows.

Josh’s father, David, recalled the problems he noticed when he helped his son move into his first off-campus apartment: dirty, obstructed stairs, a broken banister, peeling paint, and only one way out of the attic.

“We looked the other way and Josh seemed to be happy and it was a near-fatal mistake,” his father said.

Braet, 23, still struggles with anxiety and day-in day-out pain in her back. Goldenberg, who was in a coma for nearly two weeks and spent three months at the Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, missed more than a semester and suffers from double vision, balance problems, and other issues related to his brain injury.

And when the deadly fire ripped through 87 Linden St. last year, Braet and Goldenberg and their families were left in stunned disbelief that it had happened again so soon in a house right across the street.

“The landlords push the laws any way they want,’’ David Goldenberg said. “The city looks away. The universities look away. It’s a dirty little secret of college life.’’

Globe correspondents Jasper Craven, Emily Overholt, Melissa Hanson, Matt Rocheleau, and Jaclyn Reiss contributed to this report.